The Greenwich Hospital Nurses – Hidden From History

Mon 8 Mar 21

The nurses of the Royal Hospital for Seamen at Greenwich were paid, clothed and housed in return for their work and applicants had to prove that they were the widows of seamen and thus eligible to benefit from the charity. The Hospital accommodated 2710 disabled and elderly seamen at its height in 1814, assisted by 144 nurses who were managed by 3 matrons. Nurses were busy keeping the accommodation clean and aired, sorting beds and bedding, tending the fires, rationing the coals, mending, caring for those who were sick in the infirmary and, in the early days, caring for the schoolboys housed there too.

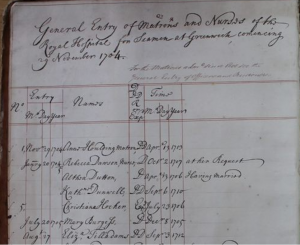

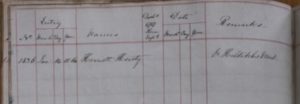

The Nurses Entry Book held at The National Archives at Kew records the names of them all and the photographs here show the first and last admissions. Between November 1704 when Anne Houlding was appointed Matron until the last nurse, Harriet Henty, arrived in 1864, 1,536 women in total were employed. The records describe the uniforms they wore and detail their duties and the rules governing their conduct. It is disappointing, although perhaps not surprising, that we have yet to discover a single image of a nurse in any of the many paintings, etchings and cartoons that picture the Greenwich Pensioners and the palatial buildings that were developed to house them.

Documents held at Kew give poignant clues about the circumstances of these widows, the numbers of children they had to support, the ships on which their husbands had served and circumstance of their death. ‘Lost at sea’ is a regular entry.

“Well behaved women seldom make history,” said Laurel Thatcher Ulrich. Some of our nurses left wills and we are transcribing them as part of a wider project, so we can glean some clues about their lives. However, most of our documentary information about them, particularly in the eighteenth century, comes from the Council minutes detailing their transgressions.

Imagine the challenge of keeping order and discipline with hundreds of retired sailors and young women living so close to the taverns of Greenwich and Deptford. Chapel attendance was required twice daily but strong drink was a powerful temptation. The minute books record the punishments for nurses found guilty of bringing alcohol into the grounds and misbehaving. For instance, in January 1707, there was a commotion in the nurses accommodation. Nurse Lester had come in late “Drunke and could not speak plaine language” and “abused Nurse Dawson very grossly and cursed & swore”. Nurse Chapman was drunk and “singing and Dancing.” The Council then issued rules stating that any nurse found drinking with a Pensioner would be dismissed. The record shows that Nurse Dawson left in October 1707 “at her own request’.

Pensioners were disciplined by systems that were familiar from their days at sea. The widows had to adjust to being managed by the Matron and abiding by the rules set. Punishments included fines, being sat in the stocks, being obliged to wear a yellow bonnet and yellow sleeve (Pensioner miscreants had to wear a yellow coat) and, ultimately, being expelled.

Most nurses, of course, led quiet and industrious lives and have disappeared from view. Many lived and died in the service, others were pensioned or returned to their home parishes to end their days in the local workhouses that provided for pauper widows. Over 150 years the charity saw many changes and there is much still to be discovered about the women as well as the men who lived in these magnificent buildings.