Henry George

A letter from Philip Stephens, Secretary to Greenwich Hospital, describes how Henry George became a Greenwich Pensioner:

‘Henry George a black Seaman…was left at this Hospital Gate on the 15th… by Lieutenant Hills who the man says brought him in a tender from Plymouth.

The man appears to be a very great object of compassion having lost both his feet and is not in condition to be moved. I desire to know…whether he may be received for the present into this Hospital…In the meantime he is subsisted by a contribution from the officers.

Dr Taylor of the Hospital has examined his case and I have desired him to attend their Lordships with this letter to testify to the man’s condition and on the other side is a memo of names of the ships in which he says he has served’.

John Simmonds

John Simmonds was a Greenwich Pensioner of mixed heritage. He may have been the son of a plantation owner and an enslaved woman. In 1803 he was pressed into service on board HMS Revolutionnaire before transferring to HMS Conqueror. The Conqueror was the ship that took the surrender of the French commander, Admiral Villeneuve, after the Battle of Trafalgar on 21 October 1805. Simmonds went on to gain the rank of Quarter Master while serving on HMS Variable.

Following a bout of yellow fever, Simmonds was admitted to Greenwich Hospital as a Pensioner in 1824. He married a White Londoner, Ann Fouch, in Clerkenwell before moving to Mansfield where they worked as hawkers.

In 1846 John Simmonds received the Trafalgar Medal. He died in Mansfield in 1858.

Samuel Michael

Born in Philadelphia, Samuel Michael worked on merchant vessels before joining the Royal Navy in 1792. Although he served until 1812, he was never promoted beyond the rank of Seaman. He became a Greenwich Hospital Out-Pensioner in 1812 and an In-Pensioner in 1832.

Little is known of Samuel Michael’s early life in North America. The last known naval ship he served on was the 36-gun frigate HMS Ethalion. While serving on the Ethalion he lost a leg and in 1812 he entered Greenwich Hospital for a period of recuperation until he was discharged from the Navy.

He married in Falmouth and brought his family to London. Unable to live on his pension of £16 per year, he turned to the merchant service where he worked as a cook until old age and disease prompted his return to Greenwich Hospital – this time as an In-Pensioner aged 64. Samuel Michael died in December 1833 having spent 50 years at sea.

John Thomas

John Thomas was born on Newton plantation, Barbados. A ‘mulatto’ (person of mixed heritage) carpenter with a large family, in 1808 Thomas alleged cruelty by a plantation manager and ran away to sea. Despite stiff penalties, ships’ captains often turned a blind eye to runaways, especially those with skills.

In 1813, in London, Thomas visited Newton plantation’s absentee landlord, stated his grievances and asked to be sent home to the plantation with a promise of ‘no stripes’ (lashes). In 1815, discharged from the Navy with a Greenwich pension, Thomas returned to enslavement in Barbados.

By 1830 the Admiralty owed Thomas £56 in pension that couldn’t be paid. The Admiralty wondered ‘how this man can now be a slave having once been in His Majesty’s Service?’. A doctor in Barbados took control of the pension for the benefit of Thomas’s children.

Frederick Zeegulaar

Frederick Zeegulaar (also known as Frederick Geasbert Zeaglear) was born in the Dutch colony of Surinam between 1775 and 1780. Records of his naval service and the ships on which he served have yet to be found.

It is understood that Zeegulaar served in the Dutch army prior to his arrival in Britain. By 1808 he had established himself as the landlord of the Cock and Lion pub in Wigmore Street, London and had married Harriet Treacher at St Martin in the Fields, Westminster.

In 1808 Zeegulaar was initiated into Freemasonry at a lodge in Bow Street, Covent Garden. The lodge was subsequently investigated by other Masons for ‘entering and crafting a Black person’. Zeegulaar, however, remained a Freemason until 1821 when, for reasons unknown, he joined the Royal Navy.

The Cock and Lion is still a functioning pub in Wigmore Steet to this day.

John Deman

John Deman was born around 1774 on the island of Nevis in the West Indies. He entered the Royal Navy as a young boy and arrived in Britain in the 1790s on Nelson’s ship HMS Boreas, having served with Nelson in the Caribbean.

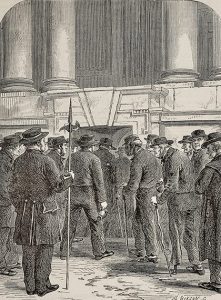

In Andrew Morton’s painting The United Service (1845) Deman appears as one of nine Greenwich Pensioners who are welcoming a party of red-jacketed Chelsea Pensioners to the Painted Hall at Greenwich Hospital. They are viewing a painting depicting Nelson’s victory at the Battle of the Nile. The nine featured Greenwich Pensioners had all served under Nelson.

Christopher Bostman

A report entitled A Black Affair introduces Christopher Bostman, a Black Greenwich Pensioner, and Belinda Watkins, ‘better known in Greenwich’ as the ‘African Venus’. She was clearly a figure of some profile in the town. Given the exchange between her and Bostman, it appears that her mother ran a boarding house, or perhaps let rooms for Black people in Greenwich. Such establishments were common in British port cities with high numbers of non-White visitors or residents.

The tone of the report and the attitude of the magistrate highlight the lack of seriousness with which Mr Bostman’s case was taken.

Briton Hammon

The Narrative of the Uncommon Sufferings, and Surprizing Deliverance, of Briton Hammon is recognised as the first ‘slave narrative’, or the first autobiographical account of enslavement. It details the trials and adventures which took Hammon through slavery and a life at sea with the Royal Navy. After several fierce naval engagements he was wounded and honourably discharged from the service. He is the first known Black seaman at Greenwich Hospital:

‘I was discharged from the Hercules the 12th Day of May 1759 (having been on board of that Ship 3 Months) on account of my being disabled in the Arm, and render’d incapable of Service, after being honourably paid the Wages due to me. I was put into the Greenwich Hospital where I stay’d and soon recovered’.